Tonight, Jeopardy will crown the winner of its Tournament of Champions. Everyone knows it will likely be James Holzhauer—or else Emma Boettcher, who in June ended Holzhauer’s 32-game winning streak. The key moment, though, has already come: On Monday’s show, instead of writing an answer to the clue (“In the title of a groundbreaking 1890 exposé of poverty in New York City slums, these three words follow ‘How the’”) semi-finalist Dhruv Gaur wrote “What is We

(The answer: “Other Half Lives.”)

Despite its wide international syndication, Jeopardy is one of the U.S.’s rare TV shows, like Saturday Night Live, that is possessed of a rich cultural relevance but fails to translate fully outside our borders, the American equivalent of television Marmite. (I’m writing this in France, where a generation of teenagers grew up with The Big Bang Theory and How I Met Your Mother.) And while it’s not impossible to stream or download Jeopardy while overseas, there’s something lonely and uncanny about the experience, like accidentally driving past your childhood home. Jeopardy is meant to be watched live, with other people—in my parents’ house in New Jersey, at 7 p.m., on Channel 7, after the dishes are done.

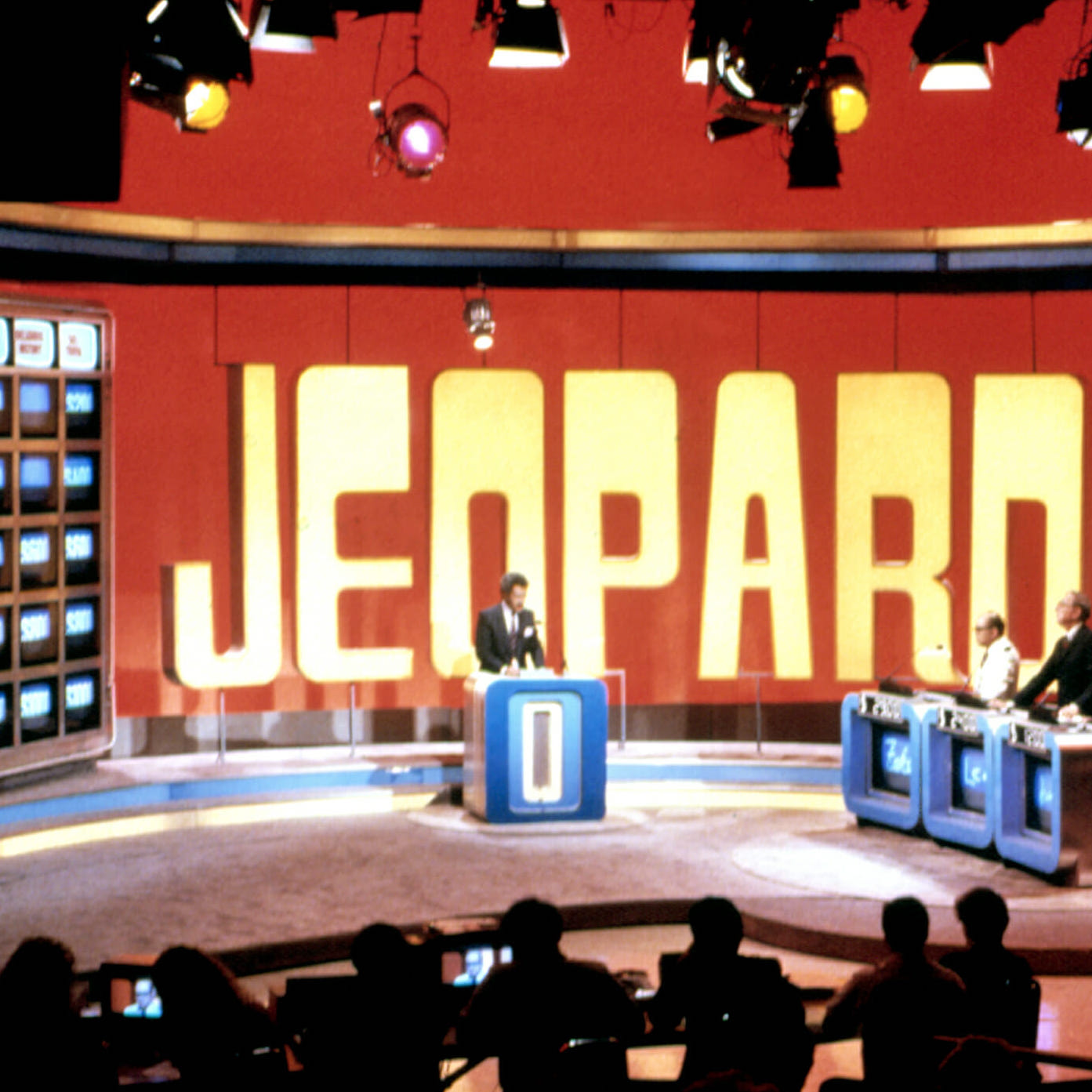

I’ve spent much of the last 10 years outside the U.S., so for me, Jeopardy is home and home is Jeopardy, something—like Thanksgiving and summer nights at baseball games—that cannot be properly replicated away from it. I can (barely) remember watching it with my grandparents at their farm in Pennsylvania, not long after Alex Trebek started hosting. Then I, along with the rest of my generation (and the generation after), grew up with the show. (Please enjoy this argument between Gen Xers, Millennials, and Generation Zs about who loves Jeopardy most.) My family has its own rules for how to watch it—primarily to refrain from saying the easy answers out loud. (“You’re embarrassing yourself,” I’m pretty sure I said to one grandstanding boyfriend, over his first American Christmas.)

Like most things that last, Jeopardy has become ever more valuable over time, along with our connection to Alex Trebek and the values they together represent: excellence, resilience, discretion, collegiality, the worth of knowledge. Those qualities have of course been magnified during a period of American history synonymous with the desecration of our national institutions, as our National Parks are sold for parts and the agencies meant to protect us now idly permit our harm (sample headline: “A Terrifying New Plan to Poison Air, Water, Humans”). Jeopardy—unlike the NFL, television news, or church—is the one place Americans still gather together, or at least simultaneously. It’s no accident that the most public and affecting reconciliation between MAGA America and Black America happened on “Black Jeopardy.” That accord wouldn’t survive the Final Jeopardy category of “Lives That Matter”—but, as Kenan Thompson’s host, Darnell, said, “It was good while it lasted.”

At a time when the baseline national mood is so consistently chaotic, it is hard not to think of what endures and what doesn’t—and to want what is good to stay forever. Of the 35 years my family has watched Jeopardy, my father has had Alzheimer’s disease for the past five. Five years ago, he could have told you how to manufacture allergy medicine. Now, if we are lucky, he will look at dark clouds gathering on the horizon and say something like, “Storm’s coming in,” and we will be grateful, because his mind has allowed him to connect a cause (the clouds) to an effect (the storm). He retains little new information from day to day—but one of the few things to stay with him was the news of Trebek’s initial diagnosis in March. “He doin’ OK?” he would ask, as we settled into our seats for the show and Alex appeared, to introduce the contestants.

“Absolutely,” we said.

“He doin’ OK?” he’d ask the next night.

“Absolutely,” we said.

“He doin’ OK?” he’d ask the next night.

“He’s going to be just fine,” we said.

And then we would watch the show, and my father, who once could have recited the periodic table of elements backward, would stay quiet—except, every once in a while, when an answer came to him, an Alexander Fleming or a Krakatoa. I did not write it down, because there is only so much wonderful/terrible I can stomach, but once this summer, he knew the Final Jeopardy answer when no one else did—not the contestants, not my mother or I. And we said to ourselves: At least something is left, for now.

We have discovered that the milestones of the disease reveal themselves only in retrospect: We did not know that that would be the last family vacation until we returned from it, and my addled father, so worried that we would leave him behind wherever we went next, preemptively packed his old work suitcase with two clock radios, a pack of AA batteries, a landline telephone, and a jumble of cables. We do not know if this will be the last time he climbs the stairs on his own. We do not know if this time is the last time he will remember the dog’s name, or my name, or his own.

I do not know if Krakatoa or Alexander Fleming will be my father’s last Jeopardy answer. I hope it isn’t: I hope tonight, he has an answer that James and Emma do not. I do not know if this will be Alex Trebek’s last Tournament of Champions. I pray my mother and I were right when we assured my father that yes, absolutely, he is going to be fine. If Alzheimer’s has taught me anything, it is that there is relief in not looking forward, not looking back. We are here. Alex is here. We are all of us together, in our way, and what can we do but be thankful for it?