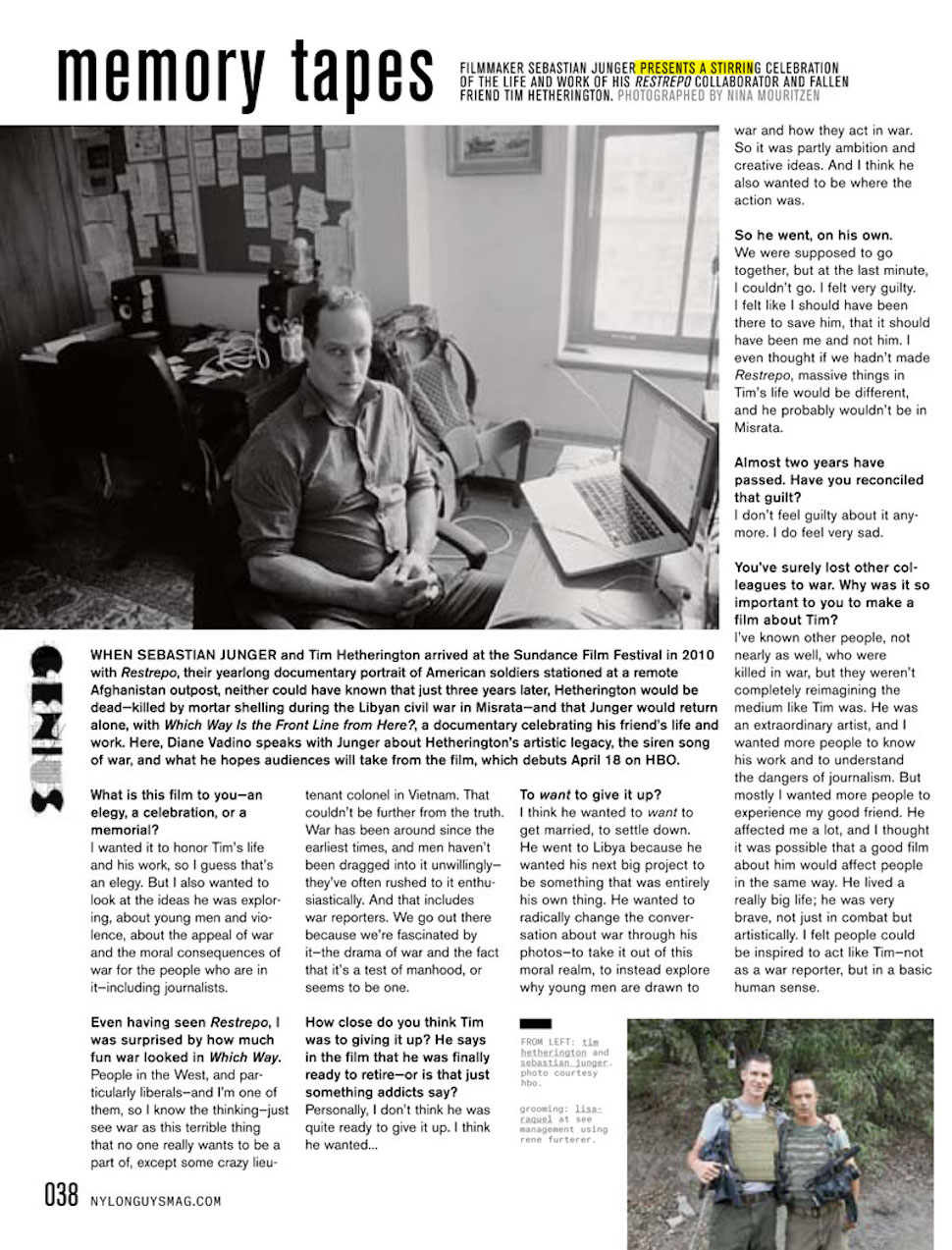

Sebastian Junger for NYLON: When Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington came to the Sundance Film Festival in 2010 with Restrepo, neither could have known that just three years later, Hetherington would be dead—killed by mortar shelling during the Libyan civil war in April 2011—and Junger would return alone, with Which Way Is the Front Line from Here?, a new documentary celebrating Hetherington’s life and work. We spoke with Junger about Hetherington’s artistic legacy, the siren song of war, and what he hopes audiences will take from the film.

NYLON: What is this film to you—an elegy? A celebration? A memorial?

Sebastian Junger: I wanted it to honor Tim’s life and his work—I guess that’s an elegy. But I also wanted it to be an exploration of the ideas that he was exploring, about young men and war and violence, about the appeal of war and the moral consequences of war for the people who are in it—including journalists.

Even having seen Restrepo [Junger and Hetherington’s year-long portrait of American soldiers at a remote Afghanistan outpost], I was surprised to see how much fun war looked like in this movie.

People in the West, and particularly liberals—and I’m liberal, so I know the thinking—just see war as this terrible thing that no one involved really wants to be part of, except some crazy lieutenant colonel in Vietnam. And that couldn’t be further from the truth. War has been around since the earliest times, and men haven’t been dragged into it unwillingly—they’ve rushed to it, enthusiastically. And that includes war reporters. We go out there because we’re fascinated by it—the drama of war and the fact that it’s a test of manhood, or seems to be one.

How close do you think he was to giving it up? He says in the film that he was finally ready to retire—or is that just what addicts say to themselves?

Personally I don’t think he was quite ready to give it up. I think he wanted….

Wanted to want to?

I think he wanted to want to get married, to settle down. All of those things he wasn’t sure he wanted but wanted to want. He went to Libya because he wanted his next big project to be something that was entirely his own thing. He wanted to radically change the conversation about war through his photos—to take it out of this moral realm, [to instead explore] why young men are drawn to war, how they act in war. So it was partly ambition and creative ideas—and I think he wanted to be where the action is. So he went, on his own. We were supposed to go together, for Vanity Fair, and at the last minute, I couldn’t go. I felt very guilty. I felt like I should have been there to save him, that it should have been me and not him. I even thought if we hadn’t made Restrepo, massive things in Tim’s life would be different, and he probably wouldn’t be in Misrata [Libya, where he was killed].

It’s been almost two years. Have you reconciled that guilt?

I don’t feel guilty about it anymore. I do feel very sad about it.

I’m sure you’ve lost other colleagues to war. Why was it so important to you to make a film about Tim?

He was an extraordinary artist. I’ve known other people, not nearly as well, who were killed in war—they’re photographers; they weren’t necessarily thinking outside the conventional boundaries of photography. They just weren’t completely reimagining the medium, like Tim was. I wanted more people to know his work and to understand the dangers of journalism—but mostly I wanted more people to experience my good friend. He affected me a lot, and I thought it was possible that a good film about him would affect people in the same way. He lived a really big life; he was very brave, not just in combat but artistically. I felt people could be inspired to act like Tim—not as a war reporter, but in a basic human sense.